Abtnaundorf Memorial – Memorial commemorating the Abtnaundorf Massacre at the "Leipzig-Thekla" Concentration Camp on 18th April 1945

In September 1958, an obelisk was dedicated in Theklaer Straße in Leipzig-Abtnaundorf. It commemorates one of the most horrific crimes committed during the Nazi tyranny in Leipzig. More than 80 prisoners were burnt to death in a barrack building of the “Leipzig-Thekla” concentration camp, or murdered while trying to escape over the barbed wire perimeter fence on 18th April 1945.

The text below provides detailed historical background information regarding the site of the concentration camp and about the Abtnaundorf massacre.

Forced Labour During the Nazi Era in Leipzig

During the Second World War (from 1939 to 1945), at least, 75,000 people were deported to Leipzig to work as forced labourers. They came from all countries which the German Wehrmacht had occupied and, in particular, from Poland and the Soviet Union. They were both prisoners of war and so-called “civilian forced labourers” - young people who had either been lured with false promises, recruited forcibly or deported and taken to the “Deutsches Reich”.

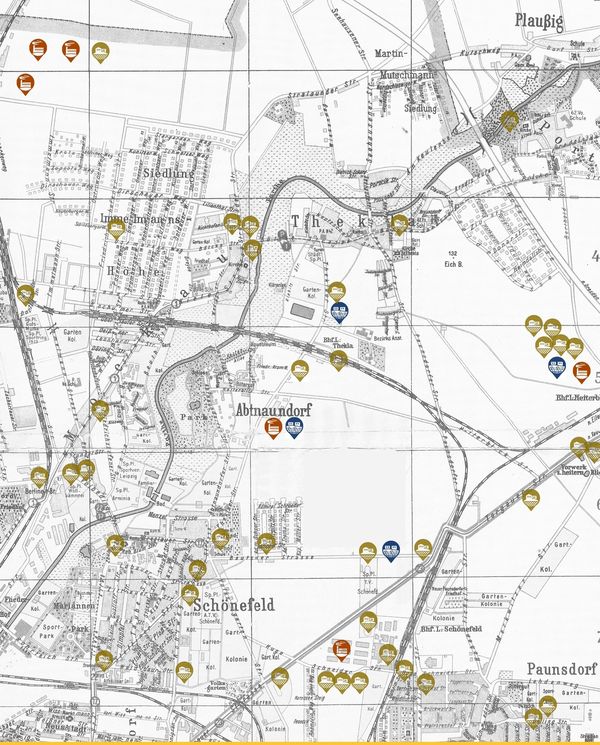

They were housed in approximately 700 collective accommodation centres within the city area – in gymnasiums, schools, restaurants, banqueting rooms, hotels, private apartments and barrack facilities.

The forced labourers were employed in all fields of business and public life: In particular, in the arms industry but also in smaller workshops, the railway and the mail services as well as in hospitals and the municipal administration and as home helps in private residences. In 1944, foreign forced labourers accounted for approximately one quarter of the workers in the German economy – without them the economy (as well as normal day-to-day life in Leipzig) would have collapsed.

The conditions under which the forced labourers lived were very diverse and depended on many factors. Their classification under the Nazi racial ideology formed an important criterion. Under this ideology, prisoners of war and civilian forced labourers from the Soviet Union (so-called “Ostarbeiter” or “workers from the east”) as well as concentration camp inmates (who included many Jews as well as Sinti and Roma) were treated worst.

From 1943, six sub-camps of Buchenwald concentration camp were established in Leipzig and its vicinity. The concentration camp inmates also had to perform forced labour in the Leipzig arms industry.

Forced Labour in the North-East of Leipzig

During the Second World War, many important production sites of the German arms industry – and, in particular, for the German Air Force – were located in Leipzig. As a result of its proximity to Mockau airport and good connection to the railway system, as well as to the “Reichsautobahn” motorway (completed in 1936), many companies established facilities in the north-east of the city.

Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft (HASAG), the biggest arms company in Saxony, moved in 1898 to Leipzig-Schönefeld, at the present-day location of the science park in Permoserstraße. This company produced, in particular, ammunition and anti-tank rocket launchers. More than 10,000 forced labourers had to work at the Leipzig factory. More information on HASAG is provided here.

Mitteldeutsche Motorenwerke GmbH (MMW) was founded as a subsidiary of Auto-Union AG Chemnitz in 1935. Their production sites were located in a woodland area between Leipzig-Portitz and Taucha. The factory produced aircraft engines, and employed up to 4,000 foreign civilian forced labourers, who were housed in Taucha.

Erla-Maschinenwerke GmbH was the biggest air force armaments producer in Leipzig and moved to the north-eastern part of Leipzig in 1934.

Moreover, production at the large arms companies also boosted the supplier and sub-contractor industry which, in turn, also employed thousands of forced labourers.

Erla-Maschinenwerke GmbH

In July 1934, Erla-Maschinenwerke GmbH Leipzig was established on behalf of the German ministry of aviation. This arms company produced more than 11,000 Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter planes for the air force of the German Reich (Luftwaffe) making it the second-biggest producer of this make of aircraft in Germany.

In Saxony, Erla-Maschinenwerke had, in total, 24 production facilities – including four in Leipzig:

• Factory I: built in Leipzig-Heiterblick (Wodanstraße 40, to the north of the workshops of the Leipzig public transport services) from 1935 to 1937

• Factory II: built in 1937 on the south-eastern side of Leipzig-Mockau airport (Stralsunder Straße 81)

• Factory III: built in 1937 at the crossroads of Theklaer Straße and Heiterblickstraße

• Factory IV: built in 1940 at the Leipzig worsted yarn spinning mill building (Pfaffendorfer Straße 31, at the present site of the tropical “Gondwanaland” hall of the Leipzig zoo).

In 1936, the Erla factories were nationalised and taken over by the state-owned Luftfahrtkontor GmbH and the Saxon state bank. Following the repeal of the Treaty of Versailles in 1935, the Nazi government accelerated the militarisation of Germany and relied on the development of new technology to achieve this.

From 1934 to 1939, the workforce at the Leipzig plants increased from 111 to 5,745 employees.

Forced Labour at the Erla Factories

From 1941 on, the Erla factories in Leipzig employed foreign civilian forced labourers. Some of them had been recruited as workers in allied Italy; however, most of them were sent by the Leipzig employment office. By mid-1941, more than 400 civilian forced labourers from the occupied countries in Europe worked at the Leipzig Erla factories. The male and female forced labourers did not receive the promised standard wages and were unable to terminate their employment contracts. In 1943, approximately 16,000 people were forced to work for the Erla factories – accounting for 64% of the entire workforce.

The forced labourers were largely housed in barrack facilities. However, the Erla factories also rented gymnasiums, restaurants and dancehalls. In total, they had 20 camps throughout the city.

The quarters for civilian forced labourers from western Europe and allied countries, such as Italy, were not guarded. However, “Ostarbeiter” had to live in fenced-in and guarded camps - which they were not allowed to leave. This racist differentiation between the different categories of forced labourers was also found in other fields: The “Ostarbeiter” worked under the most difficult working conditions and received the lowest wages and food rations. At work, they were subject to strict supervision and were punished for even the smallest offences. In the case of “idling”, they were at risk of being transferred to a work education, or concentration, camp.

In August 1941, Erla-Maschinenwerke constructed a barrack camp near the Thekla sandpit where the Jewish sports club "Schild" had been situated up until the end of 1938. In 1943, around 900 civilian forced labourers from Belgium, the Netherlands, France and the Ukraine lived there in 14 barracks.

In March 1943, the first Leipzig concentration camp was built in the southern part of this camp.

The "Leipzig-Thekla" Concentration Camp

From 1943, Erla-Maschinenwerke GmbH also used concentration camp prisoners as forced labourers. In Leipzig, the “Leipzig-Thekla” sub-camp of Buchenwald concentration camp (code name “Emil”) was set up. It comprised three camp sites each for approximately 1,000 male concentration camp prisoners with the SS being in charge of the organisation as well as provisioning and guarding the prisoners.

Initially, the southern part of the forced labour camp “An der Sandgrube” was used to house the first concentration camp prisoners who arrived in March 1943. They were forced to build the camps at the planned sites near Factory I and Factory III. In December 1943, the prisoners were transferred to the completed concentration camp near Factory III.

The new camp was directly connected with Factory III through a gate. It housed approximately 900 concentration camp prisoners in five wooden barracks. At the same time, a third site of the “Leipzig-Thekla” concentration camp (which was also designed for 900 to 1,000 male prisoners) was built adjacent to Factory I.

Most transports of prisoners arrived at the Leipzig-Thekla and Leipzig-Schönefeld railway stations, which were located in the immediate vicinity of the concentration camps.

In 1943, more than 2,000 concentration camp prisoners were used as forced labourers at the Erla factories in Leipzig. In 1944, another 1,800 prisoners were transferred from the Buchenwald main camp to the “Leipzig-Thekla” sub-camp. Among them were men from the Soviet Union, Poland, France, Belgium and Czechoslovakia. In March 1945, roughly 1,500 prisoners were still in the camps.

The concentration camp prisoners were used as forced labourers in aircraft production as well as in construction and clear-up work outside the factory premises. Almost all the workers in Factory III were concentration camp prisoners. Their work, which they performed under the supervision of the German foremen and supervisors, primarily comprised the final assembly of wing sections, control systems and landing gear. They had to work twelve hours in day and night shifts without any days of rest. Low food rations and a lack of shoes made their lives even more difficult. Seriously ill prisoners and prisoners incapable of working were sent back to Buchenwald and replaced with new workers. More than 100 people died in the camps. Others were killed during allied bombing raids of the arms factories.

The End of the War and Death Marches

After the dissolution of many concentration camps in occupied Poland in the last year of the war, another 1,000 concentration camp prisoners came to the “Leipzig-Thekla” sub-camp. The camp was crowded.

On 17th February 1945, a transport with around 600 prisoners arrived from the Gassen sub-camp of the Groß-Rosen camp. The exhausted prisoners were unable to work and were not given food as a result. “We looked for food waste and whenever we found earthworms, we simply ate them,” remembered the former prisoner, Piotr Pikulinski. 37 people died in the following days.

Between 9th and 11th April 1945, 300 Jewish women from the Hessisch-Lichtenau sub-camp of the Buchenwald concentration camp were temporarily taken to “Leipzig-Thekla”. One barrack was fenced off from the men's camp for this purpose.

Allied bombing raids on Leipzig also hit large parts of the Erla factories. With the exception of Factory III, most of the production facilities had been destroyed by February/March 1945 and, as a result, there was hardly any work. In order to hide their crimes, the factory management and the SS prepared for the closing down of the camps.

On 13th April 1945, approximately 1,500 prisoners were forced to go on a so-called "death march" on which they were joined by thousands of other men and women from other Leipzig concentration camps. The approximately 500-kilometre long march across Saxony cost the lives of many prisoners – however, some managed to escape. Only around 300 prisoners of the thousands who were forced to go on this march survived and were later liberated by the Red Army in Teplice (Czechoslovakia).

The Abtnaundorf Massacre

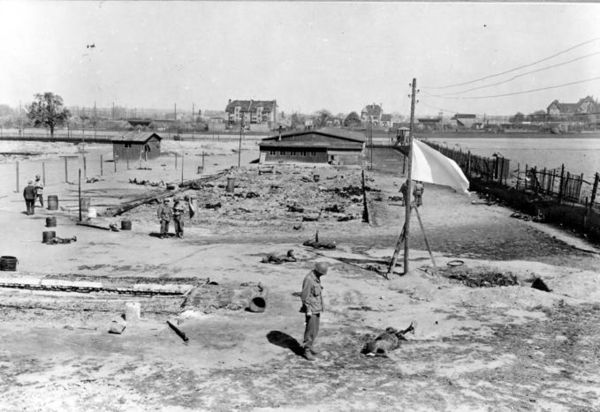

After the last roll call on 17th April 1945, 304 prisoners who were ill or dying or could not walk remained in the camp guarded by the SS. Among them were around 230 prisoners from the Gassen sub-camp who had only arrived in Leipzig in February.

On the following day, 18th April 1945, a crime took place in Leipzig-Thekla which became infamous worldwide as the “Abtnaundorf massacre”. Twelve SS men locked up the sick prisoners in a barrack building, poured petrol over it and set fire to it using grenade launchers and machine guns. Many of the prisoners who managed to escape from the burning building were killed by the perpetrators with automatic weapons. Using the dense smoke to hide, some prisoners managed to escape to the nearby living-quarters of the Polish civilian workers of Hugo Schneider AG (HASAG), who took them in and hid them. Others were shot or beaten to death by civilian residents in the immediate vicinity.

To this day, the exact number of the victims of the massacre has not been established. 67 persons are known to have survived. Most of the victims are still missing to this day. The mortal remains of 84 men, 18 of whom were identified, were buried at the “Südfriedhof” cemetery (along the central axis of the main path from the northern gate towards the building complex of the hall of worship and the crematorium) on 27th April 1945.

An investigative team of the US army that arrived only a few hours later documented and filmed the crime scene. These documents were used as evidence at the Nuremberg Trials against the main war criminals and, as a result, they became known internationally.

The Abtnaundorf massacre was committed not only by members of the SS. The perpetrators also included members of the Leipzig Secret State Police (Gestapo) and the Schönefeld Volkssturm as well as about 35 members of the Erla factory security service and fire-fighters from the Erla main factory.

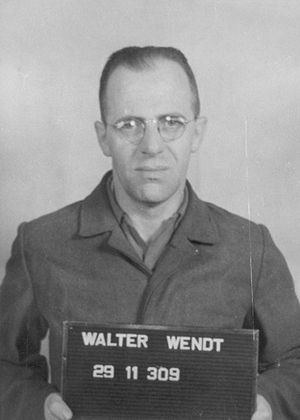

As early as on 12th April 1945 arrangements were made between the head of the Gestapo in Leipzig, Fritz Anselmi, the chief of police, Major General Wilhelm von Grolman, and the personnel manager of the Erla factories, Walter Wendt, regarding the dissolution of the camp and the removal of the sick prisoners. The director of the Erla Factories, Arno Fickert, was also informed of this. SS Obersturmführer Michaelis signed the command to murder the concentration camp prisoners.

Almost all of the perpetrators were identified and arrest warrants were issued by the US authorities by 1947. However, the court proceedings were only initiated in 1975. With certain interruptions, the investigation continued until 1990 and was finally dropped. Only Walter Wendt was put on trial in 1947.

Walter Georg Wendt

* 1907 in Leipzig

† 1977 in Filderstadt (Baden-Württemberg)

SA Oberscharführer (senior squad leader), from 1941 head of the personnel department of the Erla factories. Wendt was also responsible for the “deployment of foreign workers” at the Erla factories. In 1947, he was sentenced to a fifteen-year prison term during the Dachau Buchenwald trial. This sentence was later commuted to five years in prison.

Memories of Former Prisoners

Paul Dominikiewicz (1910-1945)

"13th April – Friday. A fateful day. An evil day. Two years of detention; and I am trying to write. Actually, when I look back I find that the months have flown by – even though the days, the hours have felt so long to me. It has been two years since I was torn away from my loved ones. Two years of misery, two years during which I have lost any semblance of freedom, during which my dignity as a human being has been stolen, to turn me into nothing but a number. How many have not made it and fallen by the wayside? I wonder what this April will hold for me. Last year, on 18th April, Henkel was bombed and I almost lost my limbs there. But I am not superstitious and hope that – to break the tradition of the past two years – this April will bring liberation and all the joys that will accompany it. I am waiting."

Paul Dominikiewicz was forced to go on the so-called death march on 13th April 1945 along with many thousand other prisoners. On 7th May, he was shot dead by a 17-year old SS “Anwärter” in Sadisdorf (near Bad Schmiedeberg).

Ryszard Jackowski (*1925 in Warsaw)

“...We could see the muzzle flashes of the automatic weapons through the cracks. We realised that the camp was being liquidated – and that we were to be annihilated once and for all. The inmates began to scream loudly. Afterwards, a hail of bullets from automatic weapons rained down on us. The shots were fired on the barrack block from the side of the camp. We began to break up the plank beds in order to have something to defend ourselves with and to help us get out of there. The doors and windows opened towards the camp and the Germans were on one side; while, on the other side, there were windows opening towards the camp’s fence. [...] So I tried to climb through the window (which someone had smashed in) on the other side of the barrack block. Crawling out was difficult; but another prisoner pushed me out from behind. Even though I fell to the floor, I got up again right away. I was surrounded by a cloud of smoke and walked directly towards the fence. I had wooden clogs on my feet, which helped me in climbing over the fence. […] Behind the fence, there was already another prisoner who helped me to climb down on the other side. On this side, there were no Germans, since dense clouds of smoke had formed. However, the direction of the wind changed suddenly; the Germans noticed us and opened fire on us from the other side of the barrack block. [...] Almost on all fours, I managed to crawl approximately 50 metres. I was very weak. When I looked around, the entire barrack block was on fire and surrounded by smoke; the roof structure began to collapse – and there were still people in the building. I saw bodies in striped clothing hanging over the wire fence – obviously, these were prisoners who had been shot or were so exhausted that they could not go on. I kept running ...”

Pjotr Korschunkow

* 1919 in Stavropol (Soviet Union)

† 2002 in Ust-Bargusin on Lake Baikal (Russia)

Photographer and sculptor, soldier in the Red Army

Korschunkow was taken prisoner of war by the Germans near Smolensk in 1942, he survived several camps and arrived at the “Leipzig-Thekla” concentration camp from Groß-Rosen concentration camp in February 1945. He survived the Abtnaundorf Massacre and returned to the Soviet Union.

"I was lying on my plank bed when I heard the cry “Fire!”. At the same time, I noticed the smell of smoke and rushed to the window. At that moment, there was an explosion and I lost consciousness. When I came to, the barrack was ablaze. I heard people screaming and machine guns firing. In spite of my injury and almost suffocated by the smoke, I crept to the window which had been knocked out by the detonation. In front of the window, there was a mountain of moving human bodies that could not get outside. Others were climbing over this mountain of emaciated and dead human beings in the hope of getting out. I also crawled over this mountain. Someone who was behind me held on to my legs. I freed myself and slipped out the window – which was already on fire. In the black smoke, you could hardly see the contours of human beings. Under the hail of bullets and protected by the dark clouds of smoke I crept to the barbed wire fence..."

Subsequent History and Commemoration

All forced labour and concentration camps of the Erla factories were disbanded by the end of June 1945. Upon orders by the Soviet military administration (SMAD), Erla-Maschinenwerke GmbH was dismantled and liquidated on 27th August 1949. Factory I and some of the camps located there had already been destroyed in the bombing raids. However, the concentration camp and Factory III in Abtnaundorf were undestroyed.

In January 1946, a provisional memorial was constructed in Theklaer Straße to commemorate the victims of the Abtnaundorf massacre. In 1957, the foundation stone for the present-day memorial was laid. This memorial is located a little off the former concentration camp. It was designed by the Bad Lausick sculptor Gustav Tschech-Löffler. It was opened in a ceremony on 13th September 1958 and has been the central venue of the annual commemoration of the Leipzig victims of national socialism ever since.

Further Information

Karl-Heinz Rother / Jelena Rother: Die Erla-Werke und das Massaker von Abtnaundorf, Leipzig 2013. Available from Bund der Antifaschisten e. V. Leipzig, Zschochersche Straße 21, 04229 Leipzig, phone: +49 (0)341 4934 731, bdaleipzig(at)web.de and at the Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial.

Report of the US Army war crimes investigation team no. 6822 dated 1st May 1945, RG338, National Archives, USA.

Imprint

Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial

Permoserstraße 15, 04318 Leipzig

Phone: +49 (0)341 235 2075

E-mail: gedenkstaette [at] zwangsarbeit-in-leipzig [dot] de

Homepage: www.zwangsarbeit-in-leipzig.de

Concept, picture selection, texts: Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial, Jelena Rother, VVN-BdA Leipzig, Siedlerverein “Moränensiedlung Portitz” e.V. [Association of the “Moränensiedlung Portitz” estate], Bürgerverein Nord-Ost [Residents' Association North-East]

Editorial team: Jelena Rother, Anne Friebel

We would like to thank Dr. Johanna Sänger and Dr. Günter Schmidt for their expertise and content-related support.

Leipzig, in January 2017